According to tradition, Noia was founded by Noah and his descendants. This legend is featured in the municipality’s coat of arms.

THE ORIGINS AND FIRST WRITTEN TESTIMONIES

There is evidence of the presence of humans in the dolmen of Cova da Moura or Anta de Argala, which is characteristic of the Megalithic culture that existed from 4000 to 2000 BC. Traces of the culture of the “castros” (fortified Iron Age settlements) not only appear in books but also in place names (Castro de San Lois, Castro de Sobreviñas or Castro Lampreeiro). However, the first written testimonies about the Noia region appear in classical writings (1st c. AD, Pomponius Mela, in his treatise De chorographia, Plinius in his work Naturalis Historia, when describing the Galician coastline he mentions the “oppidum” –fortified village– of Noega). The Roman presence in this region dates from the 2nd century BC, featuring the “per loca maritima” road, evidence of which can be seen in the medieval bridges.

THE MIDDLE AGES

In this period, Noia became one of Galicia’s main towns due to the discovery of the “Apostle’s Sarcophagus; known as “Compostela’s Port,” it experienced a great boom in its commercial activities. New population centres were created in the 9th and 10th centuries, such as Vilanova, Vistahermosa, Vilaboa, Vilar de Boa, Vilar de Ousoño or Vilarello. The expansion process would be decisive in the 12th century, with a new phase of urban development that reached its climax when Fernando II of León, on April 9, 1168, granted a new town charter; this empowered the archbishop of Compostela, Don Pedro Gudesteiz, to build a new settlement in the region of Santiago, in the area of Santa Cristina de Noia, on the banks of the Tambre River, which would be called Totum Bonum.

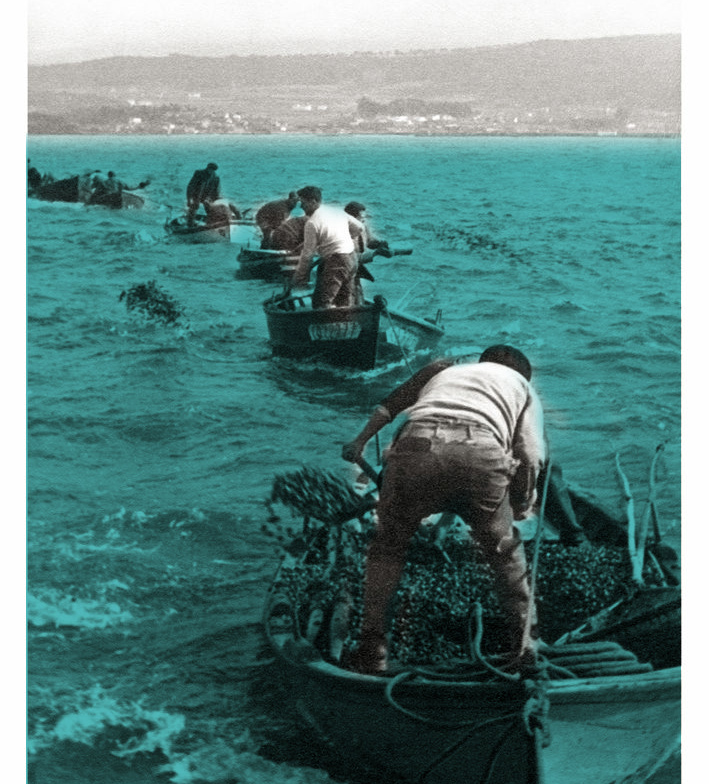

During this period, Noia became a prominent seaport, giving rise to important economic and fishing activities that would continue to increase in the following centuries.

The importance of Noia in times past can be seen in the fact that it appeared in the Luxoro Atlas from the mid-14th century, in that of Angelino Dulcert (Majorca, 1339), in Cresque Abraham’s Catalan Atlas (1375) and in that of Ortelius, which featured flourishing trade centres or historically renowned localities. Politically speaking, it is worth highlighting that Noia came under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Compostela when the Asturian monarchs granted Santiago rulership over all the territory within a 24-mile radius of the Apostle’s city.

Noia gradually acquired its present-day urban layout during the final centuries of the Middle Ages, with the construction of walls to defend the town (1320), the Tapal fort, most of the stately homes (some beautiful examples of which still remain, such as the hospitals of El Curro, Espíritu Santo and San Lázaro) or the rebuilding of the old churches of Santa María a Nova and San Martiño, the reconstruction of the old Roman bridges and the layout of the streets.

The town of Noia was where Archbishop Berenguel de Landoira held the first council “that he had with his priests.”

In the 15th century, another archbishop, Alonso Fonseca II, was imprisoned in Noia during new uprisings between the nobles and the Archbishopric. From here he was taken to Vimianzo, where he was kept in prison for almost 3 years.

More significant revolts broke out soon thereafter, this time between peasants and town dwellers against the power of the nobles and high-ranking clergy: the “Irmandiña” revolutions from 1431 to 1469 opposed the excessive ambition of the lords, who wanted to compensate for their reduced income during this time of crisis by reviving old taxes and personal loans that had been discontinued. Noia’s Brotherhood seized the Tapal fort during the assault, resulting in major damage therein. In 1476, the Catholic Monarchs agreed to return it to Archbishop Alonso de Fonseca II, who reinforced the castle.

THE MODERN AGE

In accordance with a papal brief from Gregorio XIII, Felipe II separated in 1585 several towns from the rule of the Archbishopric of Compostela and proceeded to sell them. Noia was acquired by the Genoese Baltasar de Lomelin, who governed from Madrid; thereafter, it was governed by the Genoese Sinivaldo Fiesco. In the year 1636, the town was restored to the Archbishopric of Compostela until the end of the feudal estates.

That was also the time when cattle fairs and markets, especially that of San Marcos, starting becoming important. In 1533, Noia became the Royal Navy’s sardine contracting centre for Catalonia and Portugal, which relaunched the town’s industry and trade, making it one of the most important commercial ports in the northern Iberian Peninsula. However, fatally, Felipe II sold the town to a Genoese trader in 1585, in order to obtain funds for his war projects. Under the Italian’s administration, Noia began to decline. By the beginning of the 17th century, it had lost more than half of its population, which decreased from around 4,000 inhabitants to just over 2,000. In 1636, it was returned to the Archbishopric of Compostela. However, due to the Hapsburgs’ misguided militaristic policy and the closure of the British and Dutch ports, Noia’s trade, which had been very active in previous centuries, entered a period of decline that lasted throughout the 17th century, as a result of the war contributions and continuous recruitments.

The 18th century saw the growth of a new social class, the minor nobles that subleased their land for exorbitant prices. Furthermore, the population increase that took place during this century also led to an increase in the demand for farmland. Therefore, this intermediate nobility between the landowners –the Church and absentee landlords– and the peasants rapidly accrued an important amount of income, which they used to build their rural “pazos” (ancestral homes): those of Argalo, Bergondo and, in the 20th century, that of Pena de Oro.

On the other hand, the plagues and famines of the 18th century also had an impact on our region. Therefore, by the time the reformist Bourbons acceded to the throne, Noia was completely subservient.

The efficient reformist work carried out by “enlightened” individuals led to a revival, towards the end of this century, of Noia’s sea-related industries, especially fish salting and tanning featuring small artisanal workshops, with Noia’s inhabitants becoming accomplished artisans and important exporters.

THE CONTEMPORARY AGE

In the 19th century, during the war against the French, the Spanish Parliament was convened in Cadiz, with its decisions leading to a permanent separation between Noia and the Archbishopric’s jurisdiction. In 1835, the secularisation process obliged the Franciscans to leave Noia and give up their convent, resulting in the loss of its important library.

In 1846, Noia supported the military uprising that was aided by the most important forerunners of Galician nationalism and the “Galician Renaissance,” which ended with the execution of the so-called martyrs of Carral after the defeat of the troops led by Solís. Later on, Noia experienced governmental reprisals that forced many Galician nationalists into exile (including the poet from Outes, Francisco Añón).

Shortly thereafter, during the same reign of Isabel II, the San Marcos Fair was moved to the field of San Francisco in Noia.

The 19th century saw the beginning of an important emigration process towards America, due to the high cost of living as a result of the constant increase in the price of land leases. At the end of the century, the last colonial wars in the Philippines and Cuba once again took many Noia residents into combat, including Luis Cadarso, the commander of the old “Reina María Cristina”; it was sunk in the Battle of Cavite by the indestructible battleships of a rising power, the United States of America.

The 20th century brought about important changes, including agrarian reforms that gave, in 1923, full ownership of leased land to the Galician peasants that cultivated it, in exchange for compensations that were paid for thanks to the money sent home by emigrants. Noia’s population therefore started to grow again (it had almost 11,000 inhabitants in 1930), continuing down to the present with sporadic interruptions: the civil war of 1936 led to family separations and a high number of deaths and exiles that stopped the growth until the 1940s; the population came to a standstill again in the 1960s, due to massive emigration to other European countries.

However, the new income obtained from these emigrants boosted the municipality, whose commercial activities attract a numerous population in neighbouring municipal districts, such as Lousame or Porto do Son. However, this development has not impacted the area’s industrial activities or primary sector: the countryside, stockbreeding and fishing have not been modernised –the harvesting of cockles on the coast seems to be the only importance source of income, along with the service sector.